Testing on animals has been a long-standing topic of debate in the health and cosmetics industries. For some, it is a justifiable means to an end, and for others, a highly unethical and antiquated practice, with a whole host of perspectives in between.

Tests on animals for cosmetics products and their ingredients have been banned in the UK since 1998, and a sales ban on animal-tested cosmetics products and ingredients was fully implemented in March 2013 (PETA UK). However, in light of recent government plans to phase out animal testing in the development of new drugs and treatments, the debate around the ethics of animal experiments is once again in the public eye.

Of course, universities play a key role in research for the medical and pharmaceutical industries, so how does this play out at the universities in our city?

Sheffield Hallam University. Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

The first thing to note is the divide in approaches. Sheffield Hallam University does not test on animals, and members of their staff have been influential figures in the development of alternative methods.

Dr Neil Cross is a reader in cancer biology at SHU, and part of a team of researchers working to create models of human skin and cancer cell cultures to test treatments for disease without the use of live animals.

He told the university: “As a scientist, I have been involved in many studies where animals have been subsequently used to test new anti-tumour agents.

“Many of these studies did not show effects in the animal studies as the initial testing was performed on standard cell culture methods that do not represent the in vivo environment.

“We think that our 3D cell culture methods better predict which drugs will work in vivo, so if they do not work in our 3D cell culture method, they will not be progressed to the animal phases of testing, thus reducing unnecessary animal use.”

The products have been offered to pharmaceutical companies as new research models, thus reducing the number of animals used by these companies. The team is also working with The Humane Research Trust to develop completely non-animal methods of research – allowing vegan students to complete biomedical research without compromising their beliefs.

University of Sheffield. Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

When it comes to SHU’s neighbour, the University of Sheffield, the story is very different. Whilst UoS is actively involved in research into new technologies and initiatives to reduce the number of animals used in testing, including groundbreaking research at the Insigneo Institute for in silico medicine, animal experimentation is still ongoing.

The university explains: “As part of our efforts to remain at the forefront of medical and scientific advances, which result in life-saving treatment for people with chronic and degenerative diseases, we conduct limited research using animals.”

They reiterate that animals are only used when there is “absolutely no alternative available,” and use species of the lowest neurophysiological sensitivity “wherever possible”.

Figure 1 shows the number of animals used in research in 2024, with the most commonly used animals being zebrafish, mice and rats. In total, the University of Sheffield used 36,073 animals in experiments last year.

Figure 1: A Graph showing the number of animals used in research at the University of Sheffield in 2024.

Whilst the total figure has decreased hugely from the 68,740 animals that UoS used in research in 2019, the numbers suggest that there’s still a long way to go.

In fact, students have criticized the university for using animals unnecessarily at times. A biological sciences student recalls a first–year lab which involved the use of chick embryos, simply to look at their membranes. “Is it really worth it?” they recalled thinking.

The student who wishes to remain anonymous said: “I agree with animal testing when it has a purpose and benefits my degree, but there’s definitely room for improvement and for the university to re-evaluate the situation.”

Slideshow of images from a virtual tour of the University of Sheffield’s Biological Services, accessed 27 October 2025. This section has since been removed from the university’s website.

Another student from the Zoology department shared with me their concerns about the idea of lowest neurological sensitivity that the university uses to justify its use of animals. They explained that the labs they had taken part in so far used insects, rather than birds or mammals, on the basis that they are not sentient. However, in actuality, experts are not sure that this is the case.

They said: “If we don’t know for certain, then we shouldn’t be doing it.”

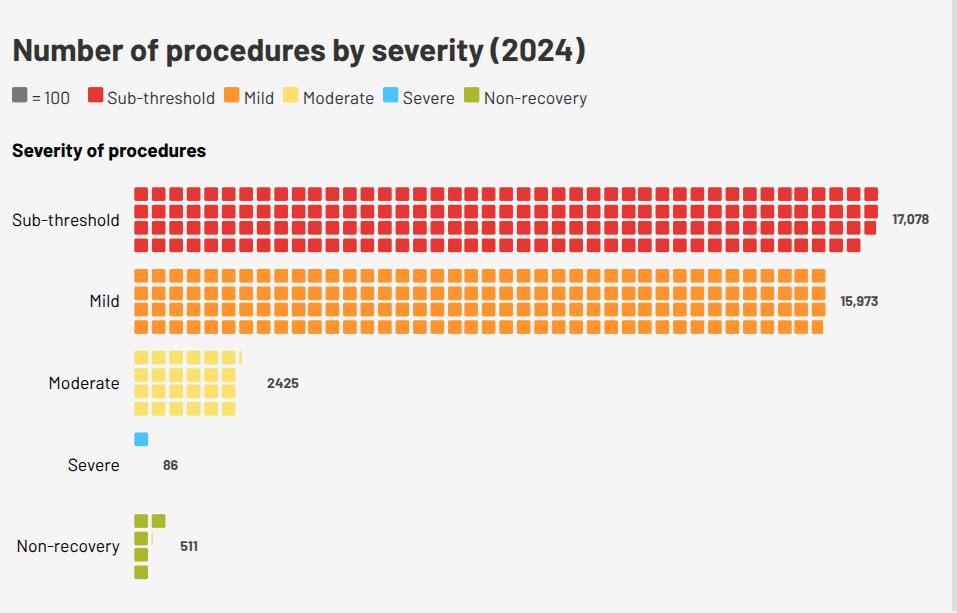

UoS also publishes data on what it calls the ‘actual severity’ of procedures performed on animals. The stages of severity, as shown in Figure 2, include:

- Sub-threshold (no suffering)

- Mild (eg. removal of blood)

- Moderate (surgical procedures eg. vasectomy)

- Severe (animal develops severe injury/disease as a result of procedures eg. MS)

- Non-recovery (procedures under terminal anaesthetic)

Figure 2: Graph showing the severity of procedures using animals at the University of Sheffield in 2024.

UoS highlights that the majority of their research falls under sub-threshold or mild – and that they conduct ethical reviews before every procedure involving an animal, via their own Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body and under the guidelines of learned societies, such as the Institute of Animal Technology.

However, others disagree with this attitude toward low-severity procedures. I spoke with committee members of Plant-Based Universities Sheffield, who are campaigning to make UoS 100% plant-based. Part of their rationale for this is combating cruelty against animals. They said: “Plant-Based Universities Sheffield condemns the use of animal testing in scientific research at the university.”

Similarly, the animal welfare charity PETA UK said: “It’s unethical for experimenters to continue to use mice, rats, guinea pigs, or other animals – who feel pain and fear as acutely as humans do.”

They added: “Teachers, researchers, and students would all benefit from modernisation, which would spare animals trauma – and potentially an agonising death – in wasteful experiments that produce no tangible results, despite the enormous suffering and loss of life.”

Plant-Based Universities Sheffield. Image credits: PBU Sheffield

This begs the question of whether the ends justify the means when it comes to animal testing. UoS legitimises the use of animals in scientific research with the potential life-changing impact of results. For example, researchers used mice to develop a new drug for motor neuron disease, which predicted safe and effective dose ranges for humans, paving the way for clinical trials and offering hope to those struggling with the disease.

However, many on the other side of the debate would argue that successful results like this are few and far between, with research by Cruelty Free International suggesting that 92% of drugs fail in human clinical trials despite appearing safe and effective in animal tests. In addition, opponents to animal testing often cite instances such as the clinical trial disaster at Northwick Park Hospital in London, where six healthy young men were treated for organ failure after experiencing a serious reaction within hours of taking a drug that had been deemed safe for human trial after testing on monkeys.

Northwick Park Hospital. Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

Ultimately, the debate around the ethical implications of animal testing in scientific research is not going to go away anytime soon. Perhaps the answer lies in open communication – between universities, lecturers and students, and pharmaceutical companies and animal welfare organisations – echoing and extending the official policy of transparency and accountability that UoS reiterates.

To find out more about the universities’ stances on animal testing, click here for information from the University of Sheffield and here for information from Sheffield Hallam University.